Free Download Rejection Sensitivity Session by Allie Duzett

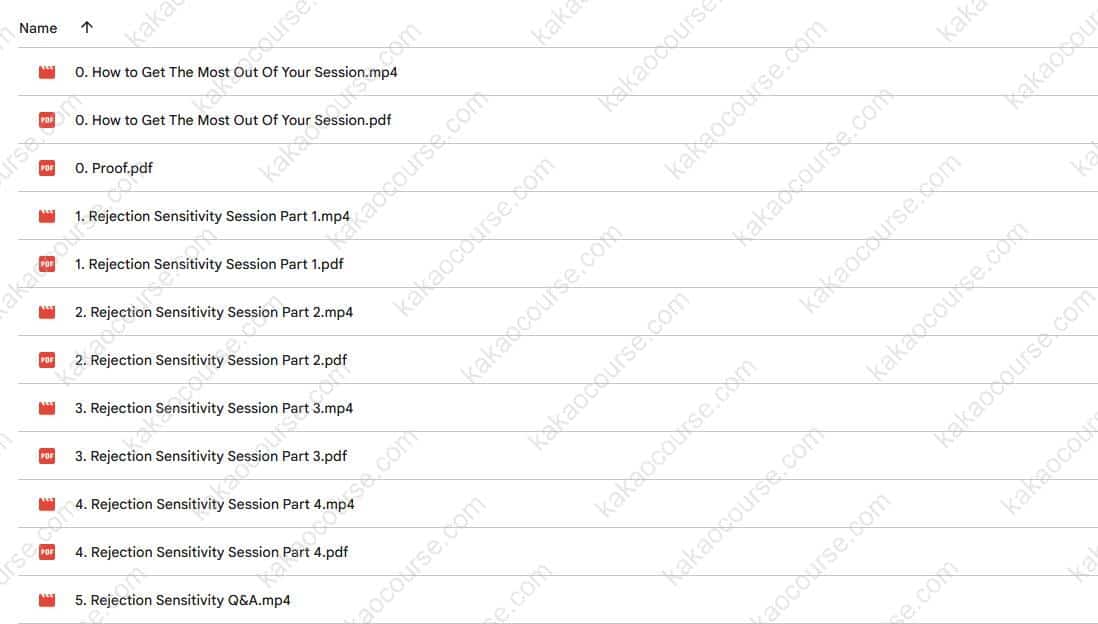

Check content proof, now:

ADHD AND REJECTION SENSITIVE DYSPHORIA

A common companion to ADHD is Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria (RSD), which involves an intense reaction to how others perceive or judge you. According to WebMD, nearly 99% (!) of individuals with ADHD experience greater sensitivity to perceived rejection compared with neurotypical people, and about a third report this as the most challenging aspect of living with ADHD.

(That said, many people without ADHD also experience RSD—it’s not exclusive to ADHD, although it is highly prevalent among those who have it.)

Let’s dive into this.

Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria is a phenomenon worth understanding deeply.

The term “dysphoria” originates from Greek, meaning “hard to bear,” and generally describes persistent discomfort or unease in life. RSD specifically refers to distress triggered by perceived rejection. In real life, this means that people with RSD often anticipate rejection and are devastated when they believe it occurs—even if no rejection actually happened. This is not a weakness; neurologically, the emotional pain is genuinely amplified in individuals with RSD.

Most people have experienced brief RSD-like feelings. For instance, someone says something to you, and you spend the next 48 hours obsessing: “Do they dislike me? What did they mean? Do they think I’m not good enough?” These ruminations and obsessive cycles of thought are typical symptoms of RSD.

Feeling rejected and sensitive is normal. The problem with RSD is that it exaggerates what should be an occasional experience. RSD transforms infrequent insecurity into intense, recurring emotional episodes.

I picture RSD as a radar in the mind, constantly scanning for potential rejection. Any perceived slight triggers a flood of negative thoughts and physical responses, like racing heartbeats or other anxiety symptoms.

Individuals with RSD often struggle with low self-esteem and set unrealistic standards to avoid rejection. “If I am flawless, nobody can reject me!” But when perfection isn’t achieved, they intensify self-criticism.

RSD can cause profound feelings of failure, emotional withdrawal, and occasional outbursts of anger. These reactions are usually about the RSD itself, not the other people involved. Understanding this distinction is crucial in any relationship.

For example, in a parent-child relationship, corrections can be seen as rejection, prompting anger or withdrawal. A child with RSD might respond to a calm reminder like, “Hey, you forgot to scoop the kitty litter,” with intense emotional reactions: screaming, blaming, or slamming the door. While this seems like an overreaction to a parent, for the child it feels catastrophic.

RSD doesn’t always manifest as dramatic outbursts. Sometimes a child quietly withdraws, feeling guilty or sad for hours, which can perpetuate cycles of uncompleted tasks and more perceived rejection.

Romantic relationships experience similar dynamics. Missed responsibilities or reminders can trigger accusations, anger, or silent withdrawal. A partner may isolate themselves with books or electronics for days before emerging more subdued or “normal.”

RSD affects relationships on both sides. Those without RSD may feel hurt or confused by what seem like random or extreme reactions, leading to misunderstandings and heightened frustration. Explaining RSD is often difficult for the person experiencing it, compounding feelings of being misunderstood.

Recognizing RSD can be empowering. Awareness helps individuals step back when feeling rejected and reassess situations realistically. Parents observing RSD behaviors in children can contextualize tantrums or extreme responses, making caregiving less confusing.

RSD isn’t officially diagnosed medically, though symptoms can sometimes be treated pharmacologically with drugs like guanfacine (Intuniv), clonidine (Kapvay), or MAO inhibitors, which may help due to underlying genetic factors affecting monoamine oxidase.

Biologically, dysphoria is linked to hypoglycemia (low blood sugar). ADHD brains also show decreased glucose metabolism compared to neurotypicals, making diet and blood sugar management vital. Many with ADHD or RSD self-medicate with sugary foods or caffeinated beverages to boost glucose and dopamine temporarily. This partially explains the higher obesity risk and soda consumption in individuals with ADHD.

Balancing blood sugar can be essential for managing ADHD and RSD. Approaches include:

-

Time-restricted eating (e.g., 12-hour eating window as described in The Circadian Code).

-

Limiting refined sugar and choosing fruit instead.

-

Consuming protein and vegetables at each meal.

-

Eating at consistent times daily.

-

Prioritizing 7+ hours of sleep at regular times.

-

Considering ketogenic diets if appropriate.

-

Detoxing with TRS, which some report improves blood sugar stability and addresses underlying heavy metal toxicity, genetics, and dietary issues.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.